Management is remarkably casual about testing the efficacy of its practices, but this needs to change, write Rob James MBE and Jules Goddard

Imagine medicine without experimentation, or pharmacology without clinical trials.

It seems impossible in today’s world. Yet, for most of history, we have relied almost entirely upon unproven, quack remedies for the treatment of illness and disease.

The story of medicine is the story, in part, of fake cures in which the unwell were persuaded to place their faith. We had bloodletting, leaches, snake oil, lobotomies and much more. For centuries we trusted in physicians, faith healers, shamans, medicine men and other authority figures to decide what was in the best interest of our health.

It is only within the past century or so that we have created a more disciplined, experimental approach to answer the two fundamental questions posed by any new treatment, drug, or therapy: Will it work? Is it safe?

These were the two questions that dominated the concerns surrounding the vaccines developed for Covid-19. The answers were provided through imagination, exploration and by impartial, controlled experiments with rigorous analysis of the results.

By contrast, management is remarkably casual about testing the efficacy of its practices. It prefers to rely almost entirely on market signals to judge its performance and on ‘best practice’ to shape its approach. Imagine the answers to the questions above if medicine, like business, had been dependent upon the marketplace and ‘best practice’ to develop its response to the pandemic. Modern medicine sets a higher hurdle for its ideas to jump than business does.

How confident are we that today’s management practices would survive the kind of clinical testing that modern drugs must pass to be made lawfully available? Is the faith that we place today in such practices any more rational than that once placed in bloodletting?

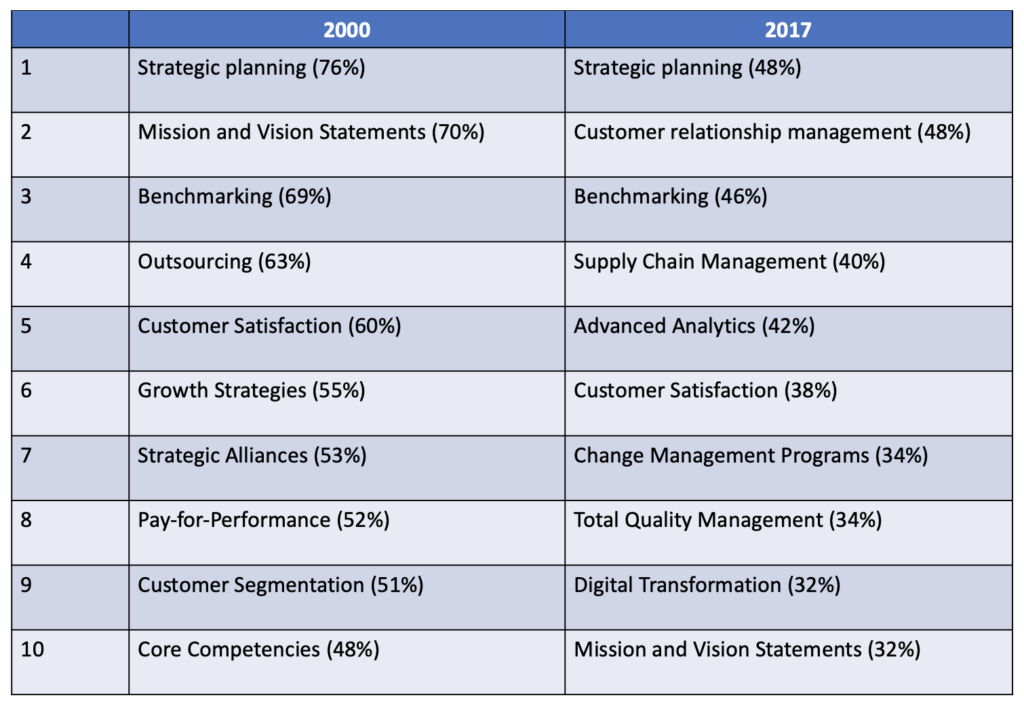

In 2017, Bain & Company’s Management Tools and Trends Survey found the 10 practices listed below to be the most relevant. But 17 years earlier, apart from the continuing presence of strategic planning and benchmarking, the rank order and the percentage scores were rather different.

Comparison of Bain Management Trends Survey 2000 v 2017

While digital transformation and economic cycles have influenced such comparisons, for many techniques, there would seem to be no rhyme nor reason to why their popularity has waxed and waned. Management practice gives the impression of being a product more of fashion and contagion than of evidence and research. By contrast, the knowledge and rational action that informs modern medicine or engineering develops gradually, systematically, and cumulatively.

With management theory, there does not seem to be the same path of progress and the result is a workplace often ruled as much by tradition and rituals as by science. Some business practices will turn out to be effective and produce value, but the majority will ultimately be shown to be overblown, injurious or mistaken. They are the 21st century equivalent of McMunn’s Elixir of Opium and other quack remedies.

So, what can business education learn from the evolution of medicine? How can a more scientific approach to problem-solving and strategic planning help to navigate the complexities and uncertainties of today’s business world?

Experimentation forces us to make our reasoning explicit

In a typical business plan, how much attention is paid to stating the make-or-break assumptions clearly and simply in a testable format? Or is it nothing more than a set of numerical targets? In each case, we are relying on rather different success factors, with business regarded as either a test of perspiration and perseverance or one of inspiration and insight.

The experimental frame of mind says: ‘Stop asking “what results and numbers do we want to achieve and what outcomes count as success?”’ These are banal questions to which every competitor in any industry will have broadly similar answers. Instead, competitive advantage begins by asking: ‘what assumptions are we banking on to deliver these outcomes, and what evidence do we have that they are true?’

Experimentation liberates the human imagination

The experimental mindset is one that relishes creativity. It is not afraid of appearing naïve, foolish or unorthodox. The importance of this lies with recognition that great entrepreneurial ideas are rarely self-evident and can be eccentric or idiosyncratic. We need to stray outside our notions of common sense if we are to bump into great business ideas.

Experimentation not only inspires people to be more imaginative in seeking options, but also to be more disciplined in their evaluation. This contrasts sharply with the standard method of strategic planning where little creativity goes into the content of the strategy and yet a spirit of ‘anything goes’ is invested in its execution… as long as targets are met.

Experimentation acknowledges human fallibility

When we start with intention, we move quickly to plans, target and milestones, missing the critical ingredients of knowledge and conceptual foundations. Experimentation starts in the right place – with what we need to know rather than what we need to achieve. It starts with our ignorance not with our desires. With an acknowledgment of our own fallibility, we find ourselves exercising curiosity, wondering aloud, listening to each other, and forming conjectures. When we ask, ‘what don’t we know that we need to know?’ it becomes the material from which sustainable strategies are constructed.

Experimentation changes attitudes to risk and failure

The list of transient practices described in the Bain report are often the result of ‘social proof’ or a herd mentality. Management techniques become popularised as people following trends or seek ‘best practice’ to avoid the risk of falling behind competitors. Sadly, they seem blind to the fact that ‘best practice’ is simply plagiarism with little being achieved by dutiful obedience. The real competitive advantage is the preserve of those who first experimented with the concept or idea. Changing attitudes to risk and failure can make the difference from being a follower to a leader.

Experimentation encourages boldness to try new ideas – to catch the first wave of innovation. It means applying a process in which risks are mitigated and failure is viewed as part of learning. It allows organisations to test strategies or new processes in discrete market segments or small parts of the organisation. By ‘farming the bets’ rather than ‘betting the farm’, it spreads the risk and creates a sense of freedom to try things out. It encourages people to test a wider span of ideas because the costs of failure are lower.

Experimentation encourages ‘agile’ competences

In science, experimentation exemplifies the virtues of patience, humility, open-mindedness, curiosity, and objectivity – qualities that are rare in most businesses where leaders are mainly rewarded and recognised for behaviours that deliver timely results and solutions. However, an over-reliance on authority, experience, and an alacrity to get the job done in these situations becomes limiting when applied in complex business environments where imagination, nimbleness and dexterity are required to succeed.

Leaders that do flourish in such an environment are comfortable with ambiguity and shun control as the only way of decision-making. They are suspicious of shortcuts, compromise and received wisdom. They seek new solutions and different ways of working. In short, they develop a set of skills and behaviours that makes them more agile leaders – they become experimentalists.

Business Experimentation – A practical guide for driving innovation and performance in your business is out now.

Rob James MBE established his own leadership consultancy practice in 2003, following senior roles in executive development at PwC. In this practice, and as a Programme Director at London Business School, he has worked globally across many industry sectors using experimentation to create greater value for businesses.

Jules Goddard is the leading proponent and practitioner of action learning programmes at London Business School. He was the first person to be appointed Gresham Professor of Commerce and now serves as a member of the Council of the Royal Institute of Philosophy.